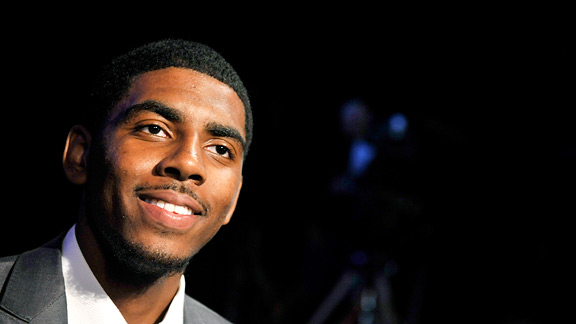

David Dow/NBAE/Getty Images

The best young players, like Kyrie Irving, are in line to take a major hit.

In Miami today, the NBA and its players union are engaged in the first day of what David Stern calls "full-blown" collective bargaining -- as opposed to smaller meetings that have been going on for weeks.

Top of the agenda: How big a hit the players will take.

It's crystal clear from both sides that the way the players and league divvy up revenues will change in this year's talks. What's being debated is whether the next agreement will be slightly less lucrative for players, or very much so.

In public, the league has made the interesting case that they will need about $800 million more a year from players, who made a little more than $2 billion this season. That number would mean, on average, that your local team would be dropping salaries by $27 million. There has been talk of a $47 million hard cap. (Point of reference: The Lakers' 2010-11 salaries topped $90 million.)

It's cheeky for the league to ask for so much while also enjoying strong TV ratings, good ticket sales and an eye-popping crop of young stars. We all know the numbers in recent years have been skewed by the recession, and even then by the league's own numbers -- which the union essentially laughs off -- the league only lost $300 million this year.

But we also know that the real negotiations are not being carried out in public, and that in past negotiations the league's real offers have come late in the process and all at once. The real number will be lower.

Just for fun, let's assume the two sides instead agree to more modest cuts for players: $250 million a year, at current revenue levels, instead of $800 million. Owners would enjoy more than half a billion in found money, while GMs would be looking to cut, on average, about $8.3 million in annual salaries. Even if that issue were settled, there'd still be a huge fight to be had, namely in how the players would carve up that smaller pie. In other words: If they can agree that players are going to give the owners that $250 million a year, the all-important next question becomes: Which players will the NBA and players union stick it to hardest?

With talk of a harder salary cap per team, rollbacks of existing deals, shorter contracts, partially guaranteed deals, and a purging of "stale" contracts (see Arenas, Gilbert), the NBA has signaled an intention to spread the pain around. History suggests, however, that one group is about to take the biggest bath: The best young players in the world.

Players on rookie scale deals

- Kevin Durant, Russell Westbrook, Blake Griffin, John Wall, Al Horford, Joakim Noah and the like played on rookie deals last year.

- In 2010-2011, 106 of 483 NBA players were on rookie scale deals.

- They make up 22 percent of the league, earning 12 percent of the salary.

- Some of the highest value deals in basketball -- many could make far more on the open market.

We're not just talking about Derrick Williams and Kyrie Irving. We're talking about every player that will arrive in the NBA over the next five or six years -- or however long the next CBA lasts.

The current rookie wage scale is atrocious for the best rookies. Blake Griffin would be a far wealthier man had he been drafted 31st and avoided the rookie wage scale that comes with being a first-rounder. (Second-rounders can reach full free agency, and earn market rates, years earlier.)

If he wants to maximize earnings under the old deal, Griffin will have to play seven years -- an eternity for an athlete -- for the wacky Donald Sterling. If Griffin follows the old path, he'd sign a three-year extension a la LeBron James and Dwyane Wade after his fourth year, meaning he'll first hit the free agent market when he's 27. By some analyses, NBA players peak as young as 24.

At $5.4 million last season, Griffin could be earning $10 or $20 million a year below his market value.

Below-market contracts already dissuade players like Ricky Rubio, who can make more elsewhere.

Meanwhile, it's an open secret in the NBA that one key to good cap management is to accumulate as many players as possible on rookie contracts. The Thunder's Sam Presti has written the book on this in recent years -- Kevin Durant, Russell Westbrook, Serge Ibaka and James Harden are just half of Oklahoma City's eight rookie scale deals last season.

How did we get here? Why did this influential group of players, which includes almost every single future NBA player, agree to such a deal? The answer is that they did not. The rookies lose collective bargaining in no small part because current NBA players vote on the CBA. Future players and incoming rookies do not vote and are well outside the process.

Chauncey Billups recently told ESPNNewYork: "A lot of these young guys don't really know anything about that. They just hope there's not a lockout. They don't have a clue about none of this stuff yet."

I asked Irving if he was sweating the CBA talks, and he said that while he had been following the news, he's "not really concerned. I know whenever it is, they'll get it resolved, and there will be an NBA season."

There has long been talk that one day some rookie or another would sue for a place at the bargaining table. But until then, their fortunes are tied to the votes of veterans. Back in a friendlier time, when CBA negotiations were about sharing profits, those players stuck it to rookies. Now the talk is much tougher, about sharing losses. A dollar taken from rookies this time around goes directly toward keeping veterans from having to live with cuts to contracts they have already signed. Although it's hard to find anyone who questions the seriousness with which Hunter and the union represent all players, it's hard to imagine rookies are about to become a higher priority than they have been in the past.

Superstars on max deals

- Chris Paul, Yao Ming, Kobe Bryant, Carmelo Anthony, Dwight Howard etc.

- In 2010-2011, 17 of the NBA's 483 players had max contracts

- Those 17 players earned about 14 percent of all NBA salaries.

- Economists suggest that the league's handful of superstars are worth several times what they are paid.

In the last lockout, there was a lot of talk about mega-stars like Michael Jordan and Patrick Ewing having all the clout. The reality is that they do make the most money, but they are also right there with rookies as the biggest losers of collective bargaining.

In a free market, the NBA would look more than a little like the movie industry. They pay Tom Hanks $20 million or more per movie because his name alone sells tickets and DVDs. After that, it almost doesn't matter who else acts, and there's no shortage of people just dying to work with Mr. Hanks for the union's minimum scale. Like it or not, that's the free market at work.

In terms of real market value, those big name NBA players are worth 10, 20, maybe even 50 times as much as their excellent and hardworking but -- in terms of the entertainment market -- replaceable teammates.

The players union exists, however, in no small part to protect the middle class, and it does a great job of that. Kobe Bryant might really generate the TV ratings, ticket sales and the like to be worth 30 Derek Fishers. But the current CBA caps Bryant's deal well below his true value, and requires teams to pay veterans like Fisher above market value. So Bryant makes only about six times as much as Fisher.

I'm not asking you to weep for Bryant, who made close to $25 million this year in NBA salaries alone. But I am asking you to acknowledge that the collective bargaining process has hurt players like him in the past, and will again -- hard. How do I know this? Because 17 votes combine to mean less than nothing. The hundreds of middling veterans, who don't sell a lot of tickets but do drive a lot of votes, are the only voting bloc that matters, and they have no reason to go to war for the multimillionaires.

What that means for Kyrie Irving is that if he's absolutely mind-blowingly fantastic, he can expect to waltz from his well below-market rookie deal into a well below-market maximum deal.

Also, as the players who earn the most, they have a nearly impossible task earning sympathy from the public, colleagues, or anybody else -- and some economists' suggestions that James may be worth many times his current salary bothers few.

We know that LeBron James, Dwyane Wade and Chris Bosh -- who are playing for less than the maximum, as it happens -- are cash cows any owner would love to have on their rosters. From the day of The Decision, the Heat have been awash in ticket sales, in-arena sponsorships and local cable subscriptions and more. The incremental increase in local revenues alone justifies the cost, to say nothing of driving the TV ratings of the entire league.

And yet those very three were singled out on Tuesday by deputy commissioner Adam Silver as examples of players the league can't afford: "The three key players on the Heat," Silver volunteers, "all have 10� percent per year increases built into their deals for next year, at a point when revenues in our business are growing somewhere around 3 percent. It's a broken system."

The union similarly places a low priority on bridging the gap between market value and maximum salaries.

"We don't have a problem with LeBron making $30 million or whatever it is," says Players Association executive director Billy Hunter, "as long as they have money to pay everybody else. Basketball is not a one man game. So, everybody else has to be paid."

They absolutely don't have that money in 2011, so, it's a good bet players like James -- and in the years to come, if he's as good as advertised, Irving -- will subsidize their teammates more heavily than ever in the future.

Earlier we speculated that players would be giving back $250 million in annual revenues under a new CBA -- about $8.3 million per team. You could get all the way there without touching the income of the 360 "other" players who can dictate the union's voting, simply by halving the value of the contracts for the quarter of all players who are on maximum or rookie deals. That's not what's going to happen, which is good news for the likes of Irving.� But the bad news is that everyone involved knows that the key to getting the players to agree to a new CBA is to appeal to the rank-and-file, who'll have strong incentives to protect their own smaller incomes at the expense of the best young players.

Source: http://espn.go.com/blog/truehoop/post/_/id/29223/young-superstars-will-feel-the-next-cbas-sting

Jud Larson Memphis Grizzlies Lamar Odom Dwayne Wade Cleveland Cavaliers Elliott Sadler

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿